My cab broadsided another cab in an intersection, and my face slammed into the plexiglas divider, my nose broke, and my mouth was severely cut on the coin cup. When the ambulence arrived, the police told my cab driver to hold my purse and stand over there. When I was extracted from the cab, he told me he was very, very sorry.

I was rushed through busy Manhattan streets to the hospital. Halfway there, the paramedic agreed to first, stop in traffic, step out of the ambulance, to call my husband from a pay phone, and second, hold my hand the rest of the way because I was shaking uncontrollably with fear.

Days later, back at home in our Hell’s Kitchen apartment, I bathed in the warm love and generosity of New Yorkers, which included a phone call from my doctor:

“Okay, it’s been three days, so now you have to get dressed and go outside for at least half an hour.”

The last time I saw my doctor was after the collision, early in the morning, in Bellevue Hospital. Lying on a gurney, I waited in the hallway with my husband at my side for hours, along with a steady stream of other patients, waiting outside the Emergency Room, including one young man handcuffed to a chair and two police men hovering nearby.

My doctor was a short, Greek-American man born-and-raised in the Bronx, dressed in a tuxedo. On call that night, he had come across town from some critical award ceremony to help me. He patted my arm and said:

“Okay, we are going to put your face back together. No worries.”

In ice cold temperature, wrapped in two wool blankets, I was told to sit upright very still for close to an hour while an intern doctor stitched my cuts back together, and one time, my doctor entered the room and told him to take out the stitches and start over, which because after years of sobriety, on this night my body was filled with medicinal morphine, made me sob.

“Believe me,” my doctor said, still wearing that tuxedo, “if we do it right, the scar won’t show. Let him take it out and do this again, but do it right.”

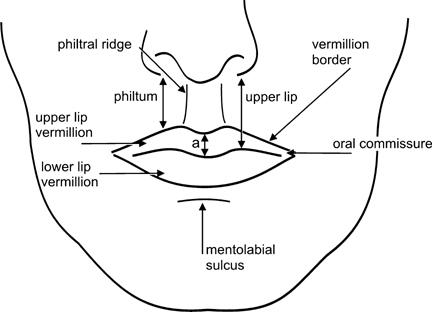

He was right. The scar traces the philtral ridge near my mouth, and is hardly visible.

So three days later, this friendly phone call from my doctor, his prescription to go outside and take a walk, was a deterrent for any more psychological trauma, akin to Time to get back up on the horse.

I made a plan to walk to the end of our street, get some food at the Deli, and then head back home. I had two black eyes and a bandage, leaking with cotton stained by orange antiseptic liquid, wrapped around my head, face, and nose. I knew, after all, this was New York, where most people mind their own business, and that no one passing me on the sidewalk would bother me.

The doorbell ting-tinged, and our dear friend from the Middle East came around from his caged-in counter, asking a million questions about what had happened. He refused to accept any payment until I returned to work.

On the way out the door, I saw and heard the engines racing–a long line of yellow cabs waiting for the light to turn green–and I swallowed hard.

At home in our apartment, while my husband was at work, my neighbors took care of me, too. The Indian Mother and widow, along with her three small daughters, who lived in the apartment across the hall, would leave plates of coconut rice and sweet desserts near my door. Our friend and neighbor, two floors up, would check in on me every hour and once a day walk me up to his apartment so we could watch television with my head held up straight, to avoid blood clots. My private home clients were leaving messages of concern. I started to receive cards and letters, many from my fellow waiters. The list went on.

And every day, I heard from my doctor, and every day, I walked further and further up the street from my house. Eventually I took my first cab ride since coming home, with my husband’s right arm securely wrapped around me, and his left hand holding and kissing my hand, to see my doctor and make plans for more surgery.

There’s much more to this story, and believe me, I know how my accident could have been much worse. And now, years later, I still feel blessed. I would not have wanted to miss this life for anything.

Leave a comment